The art of the bug

Failure should be fun.

February 2015

How should I learn to code?

There are hundreds of books that teach computer programming to novices. They usually start with "hello world" and culminate in a well-described small project. If you're just starting out, this first program may be your window into a new career; if it's effective, you'll be hooked for life. If the experience is demoralizing and alienating, our community has squandered your potential.

The tricky part is that the computer has no idea that you're just a beginner. It's not your kindly French 101 teacher who smiles through your mismatched tenses. The computer will be just as unforgiving with your first line of code as with your millionth. You're dependent upon those first few programs to set you on the slow road to mastery without breaking your spirit.

Here are some first projects from some popular learn-to-code books:

- A blog (PHP for Absolute Beginners)

- A blackjack simulator (Head First C)

- A text adventure (Learn Python the Hard Way)

- A payroll system (Java: How to Program)

These are all fine starter programs---I taught myself BASIC by writing text adventures, and blogs are the de facto sample project for every web framework. These books are well-written and pedagogically sound. But I'm convinced by a different approach entirely to your earliest software project.

How should I learn to code?

You should write a videogame, and you should write it in JavaScript.

JavaScript?

There's a lot of history in how it went from a punchline to the New Hotness, but you shouldn't learn JavaScript because it's suddenly---finally---cool. You shouldn't learn it because it's better designed than other languages (it isn't), or because it's more approachable (it's not). You should start with JavaScript because it's installed everywhere, runnable with nothing more than a web browser, and because your work can be instantly shared with anyone in the entire world.

Videogame?

Last fall Paul Ford inspired a fit of nostalgia for early 90s website hosting and aesthetics with his tilde.club project. I got it into my head that I should make a web page that looked like it was from 1995 but would do something unexpected and seemingly impossible. I wanted it to be so unexpected that it couldn't even be implemented today, not in any kind of traditional way.

This meant going outside of my normal area of expertise of web developmen—to make a little toy that look liked a website from Geocities but actually moved and reacted like something very different. (—ed. it's no longer online but I think you'll get the gist of what it did as you read on.)

It didn't end up being funny as it seemed in my head, but I enjoyed coding it more than any other program I've ever written, even though at times it was pretty difficult. Getting the program exactly right was tedious and frustrating, but getting it wrong along the way was a lot of fun, because while it looked like a web page, was actually a videogame.

Joy-driven development

If you become an exceptional programmer, 10% of the code you write will be correct. The rest will be an embarrassment of typos, compiler errors, runtime exceptions, race conditions, and unscalable hubris. If being a programmer were like being a line cook, half your customers would get botulism and die.

When the best you can hope for in your career is only occasionally typing something other than completely useless garbage, imagine how dispiriting it is to be an utter novice, when everything you do is wrong?

When I was learning to program those text adventures, error messages were cryptic:

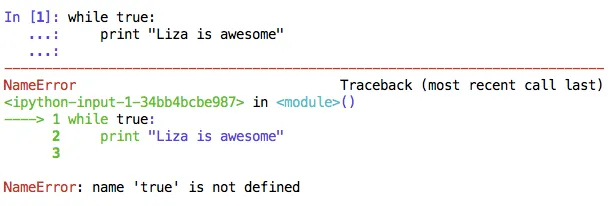

Look how far we've come with modern, friendly programming languages like Python:

And we wonder why young people aren't lining up to spend eight hours a day wrestling with the likes of ipython-input-1--33bb4bcbe987 and NameError. We have work to do if we're going to make a student's introduction to programming actually fun.

I've been a professional programmer for twenty years, so I am an exceptionally prolific generator of bugs. Most of them are boring and obvious and swiftly corrected. Many of them required help to solve. Some are still lurking, undetected. At rare moments in my career, I've been stubbornly proud of my bugs. I even have a favorite---it involves Roman numerals and dead British aristocrats---but whenever I rhapsodize about it, people remember they need to be somewhere else.

Most games involve simulated physics, and when physics are violated, hilarity ensues. You can get a feel for this when browsing collections of commercial game glitches (the apex of which is Breaking Madden). Glitches demonstrate that at even the highest levels of budget and ambition, a computer will still find ways to humiliate you.

For my project I wanted to make something that looked like a website but violated all expectations of how HTML works. I turned to Phaser, a rich and well-documented HTML5 game engine that uses plain old JavaScript to create high-performance 2D games. Phaser is trivial to learn if you've ever made Flash games (I haven't), or if you're familiar with the basics of 2D graphics and physics (I wasn't). The only thing I knew was JavaScript.

Phaser's introduction is very, very gentle (though still a bit too complex for a complete non-developer), and its main tutorial is a tractable guide to making a respectable game. The tutorial doesn't cover every aspect of Phaser, but it's way beyond "draw the rest of the owl." I was up and running (and tripping and falling down) in a couple hours.

Here's what happened when I made the world area too narrow to fit all the letters neatly across:

For a long time I was stubbornly struggling to prevent the letters from falling under the divider because I thought it violated my grand aesthetics. In the end I decided to get over myself, because when they slid under they turned the divider into a bouncy see-saw. I spent an embarrassing amount of time doing this over and over again because it made me laugh:

And at some point I made what seemed like an innocent change, and it started doing this. It took me days to understand the bug:

In order to get the effect I wanted, I had to use the most advanced of the three physics engines that come with Phaser, and it's been a long time since I struggled through high school physics. If I wasn't sure how something in Phaser worked, I could just try it and see how the game world responded. When I got the code right, I got the satisfaction that comes from slow mastery of a domain. When everything on my screen flew away because I'd accidentally inverted gravity, I could laugh and show my husband this hilarious thing I'd made.

While I was constantly doing stupid things, I never felt stupid. In a way it made me miss high school physics. If I'd studied springs and angular momentum in the context of game programming, I might've actually retained something.

I'm no expert in teaching programming, but I've attended a few no-experience-necessary tutorials as an observer and mentor. I rarely see first-day students struggling with the actual coding; that comes later. Instead I see them utterly at sea with the prerequisites that come with "real" programming languages like Java or C# or Ruby. First, install an editor---or use Notepad and God help you if you make a syntax error. Then, install the interpreter or compiler. I know the tutorial was just called "Python" but it's really Python 3 and you have version 2. Find the command line. Oops you're on Windows, you'll have to download a command line. Then set up a web server. Now draw the rest of the owl.

The reward for the dedicated learner who gets through all of that is a text-based payroll simulator which you can't even show to your friends without making them go through all that same installation junk.

By themselves, Phaser, and other JavaScript game libraries are not going to teach you to code. You'll still need a guide, whether it's a tutorial or a class or a kindly mentor. And games aren't the only way to learn programming that can be intrinsically rewarding; Minecraft and robotics and Arduino share many of the same characteristics. Any of them are a good choice for a curious beginner.

Try JavaScript, so you can share what you made with the world. Try a game, which is colorful and visual and will be so satisfying when it works. And you'll have fun the million billion times that it doesn't.

Update Jan 2020: the original project is gone, but I dusted off the concept again a few years later for "A Physical Book."