Natural language processing for programmers

Learning NLP through experimentation and public failure

March 2016

Introduction

I recently left my job to be an independent software engineer again. One of my objectives for my newly acquired free time was to increase my understanding of Natural Language Processing—the art and science of using computers to manipulate text—since human words are a thing I'm interested in.

This plan comes with some challenges:

- NLP is a huge discipline. Deciding to learn NLP is like announcing, "I want to know medicine." (I probably won't kill anybody when I make mistakes, though.)

- NLP requires a lot of math and my math skills are poor. It often surprises non-programmers to hear that you can get pretty far in a technology career without knowing a lot of math, but there's a difference between programming and computer science. I'm a good programmer but a lousy computer scientist. I'm going to have to get better at computer science, which is difficult as I hate doing things I'm not already good at.

- I'm used to having colleagues who review my work before it goes public and I embarrass myself. Now it's just me and my dumb ideas that stay dumb unless I put in some kind of effort.

How I'm doing this

When I'm successful at learning a particular NLP technique, I'll release a project that uses it, probably in the form of a small Twitter bot or online toy. When I'm unsuccessful or hit a dead end, I'll write up a postmortem, which I hope will accomplish two goals:

- Give myself a reason to release even failed experiments by talking about how they failed and what I learned. In doing so I'll probably get a better understanding of where to go next.

- Help other programmers like me navigate this discipline. At some point in NLP work, you'll google something and 100% of the results will be jargon-filled academic paywalled PDFs. There isn't the same tradition of step-by-step tutorials that we have in the web tech world, and while I'm not writing those either, I hope what I do write is helpful to others looking to get started or just get an overview of the field.

Language models versus neural nets

The cool kids are using deep learning/neural nets for NLP, as a lot of the traditional approaches seem to have reached their limit of effectiveness. But neural nets are their own thing with their own math, and while I'll get there eventually, I decided to start with pre-existing language models and statistical machine learning, both of which are better documented right now. That said, neural nets are super-interesting; see Ross Goodwin's Adventures in Narrated Reality for a fascinating exploration of using them for narrative text, from an artistic/writerly perspective.

Libraries versus APIs

I'm making a totally arbitrary decision to avoid using APIs like Erin McKean's fantastic Wordnik even though I'd certainly get better results for individual projects with it. But I'm not avoiding high-level libraries like Spacy or TextBlob in favor of rolling my own everything. I just happen to think that this will be the right mix of approachability/detail for my skill level.

Categories of Natural Language Processing

There are lots of formal categories in NLP, but here's how I bucket the different tasks:

- Parsing: Feed text to a computer and turn it into useful data. This can range from simple metrics ("Which words appear most frequently?") to building true language models ("This sentence is made up of a proper noun, a past tense verb, and a direct object.") Parsing can be treated as a programming problem rather than a computer science problem—there are very good libraries you can use as black boxes. But there are dozens of these libraries and it's not always obvious which ones to use for what task, so I'll always mention what I used and why.

- Classification: Classify what the words, sentences, or whole work mean. Some of this work can be done for you by the libraries straight out of the box, like entity recognition ("Is this a place name or a person's name?"). A common form of classification is sentiment analysis ("Is this sentence positive or negative?"). Again, that can often be done with pre-trained libraries. Custom classification means you teach the computer to differentiate sets of texts based on a particular feature you care about ("Is this a book about programming or a book about business?"). This is machine learning, and can either be done by statistical models, or neural nets. I'll do some of this.

- Production: Teach a computer to make new text. Usually (though not always) you want the computer's productions to resemble what a human might utter. Deep learning techniques are probably the best choice for large-scale artificial language production, but that's off the table for me right now. I figure it's healthy to learn the traditional tools first and understand their limitations.

Staying motivated

I'm no longer convinced that "ship early and often" is the best way to build a great product, but it's definitely a good way to learn things. If I waited until I knew everything about a particular discipline before trying it out in public, I'd get bored and despondent. Most of the code I'm going to write will be completely buggy and terrible, so I have to find a way to make the bugs fun.

Actual computational linguist Michelle Fullwood mentioned to me recently that she was using fanfiction as corpora in her work. Fanfic is an awesome source to work from: it's in the modern vernacular (versus public domain texts), it's available in vast quantities, and it's fun to work with because it can be silly and includes lots of implausible sex scenes. Most of what I produce will be stupid nonsense anyway, so starting with less serious source material increases the likelihood that I'll have fun while screwing up.

Text generation with context-free grammars

Fanfic-powered episode summaries

I started with the idea of a Twitter bot modeled after @TNG_S8, a human-written parody account which purported to summarize episodes of a non-existent season of Star Trek: The Next Generation. The best of them were just shy of being plausible.

The disappointing X-Files Season 10 has just ended, so that seemed like a good candidate for such a similar kind of account that wrote its own stories procedurally. (Back in the 90s I wrote some X-Files fanfic, which brings up the extra-meta possibility that my bot would harvest my own writing for itself.) Though X-Files was the target output, I wanted to write software that was generic enough that I could feed it any fandom and get something plausible back (especially if it happened to be a police procedural whose episodes tend to summarize consistently).

Short episode summaries follow a predictable kind of pattern:

- Episode set-up — typically this is the cold open plus Act 1 of the show.

- The A story — what the primary character or characters do in response to the setup.

- (Often) the B story — anything else that happens in the background, typically a secondary character or long-term arc.

Some real-life examples:

X-Files: When a French salvage ship sends a diving crew to recover a mysterious wreckage from World War II, the crew falls prey to a bizarre illness and Agents Mulder and Scully join the investigation. The investigation leads to the discovery of a familiar face, and to Skinner's life being threatened.

Law & Order: Detectives Lupo and Bernard investigate when an aspiring musician is found dead. A bag of cash leads them to multiple suspects.

Bones: An escape artist's body is found in the woods, and it's revealed that he may have had enemies in the magic community. Meanwhile, Brennan and Booth ask their friends to opine on their tooth-fairy debate; and Angela continues to work on her photography with Sebastian Kohl.

CSI: A robbery at a grocery store results in a shootout leaving five dead. The police officer at the scene believes Grissom has a grudge against him. The entire team has to process the enormous amount of evidence at the scene.

I decided to try to write a template that I could fill with human words derived from the fanfic corpora. The template couldn't know anything about the show itself, relying only on the source material to make something identifiably "X-Files" or "CSI"-like.

I learned that a tool I could use for the production side was a Context-Free Grammar. CFGs are best explained by example; you can think of them as "advanced Mad-Libs":

S -> SUBJECT VERB NOUN

SUBJECT -> "Cat" | "Dog"

VERB -> "bites"

NOUN -> "man"

If I "generate all productions" for this grammar, I'm saying I want to see every possible sentence that's valid. I'd get this:

Cat bites man

Dog bites man

"Cat" and "Dog", or any term in quotation marks, are called terminals in CFG lingo, but as a programmer I just think of them as constants. Punctuation marks do what you'd expect: "|" is OR, and "->" is like variable assignment. All other terms are non-terminals, or variables. The power of CFGs come in expanding non-terminals into other non-terminals:

S -> SUBJECT VERB NOUN2

SUBJECT -> "Two" PLURAL_NOUN PLURAL_VERB | "One" NOUN VERB

PLURAL_NOUN -> "cats" | "dogs"

NOUN -> "cat" | "dog"

VERB -> "bites"

PLURAL_VERB -> "bite"

NOUN2 -> "man"

SUBJECT now expands out to two possible phrases, so all the productions for this grammar would be:

Two cats bite man

Two dogs bite man

One cat bites man

One dog bites man

My CFG is a bit too long to quote, but I ended up writing a grammar that would produce summaries like this:

Variation 1: When <something> <verbs> <a thing>, <main character> <verbs> <another character>. <Main character> <verbs> <something else>.

Variation 2: In <some place>, <subject> <verbed> <a thing>. <Main character> <verbs> <another character>. <Main character> <verbs> <something else>.

Context-free grammars are nearly as old as computer programming. Originally defined by Noam Chomsky to describe human language, they were much more successful in defining non-human productions. Note that CFGs know absolutely nothing about grammar rules; pluralization and agreement have to be done by dumb substitution. This makes a CFG a lousy way to produce flexible English prose, but it's suitable for non-human grammars (like computer languages), or possibly very short, canned human-ish sentences (like bot responses).

I'd hoped to get around their limitations by assembling the input from larger units than just random word lists, but I ended up being disappointed in the output after a few days of solid work:

X-Files: In Maastricht, the dark mascara trails responded. Mulder knows things.

Law and Order: When tragic circumstances returned, Mike knows Melnick than a little. Jack means some unfinished business.

Bones: When the blackened skeleton laughed, Booth is the right anterior femur. Brennan gets far worse bodies.

CSI: In Las Vegas, the redhead believed. Grissom does Horatio below a casino. Catherine goes the first time.

These specific examples made me laugh, but the overall hit rate was lousy — most of the sentences were just a garbled mess, less plausible than if I'd used the more common approach of Markov chains, though better in the sense that they fit my predefined grammar. An ideal procedural Twitter bot makes utterances that are almost plausible. These were too random.

At this point I decided that this was a dead-end project (I was starting to not have fun), but here's what I got out of it:

- I learned how CFGs work and how to construct them. Even thought this didn't "work", I think they're still pretty useful! They're very concise representations of possible utterances and declarative, domain-specific languages are almost always better than procedural code. Without them I'd have written 30,000 unreadable lines of string concatenation garbage.

- Because CFGs are older than dirt, a lot of my research took me back to the earliest papers on language generation, many of which assumed that full-blown AI was just around the corner. I particularly liked The Possible Uses of Poetry Generation (Milic, 1970) because of how unabashedly opinionated it is: "Dylan Thomas, whose fame in the United States is puzzling and cannot wholly be ascribed to the drinking habits he displayed during his journey there."

- Some of the parsing-related tasks worked pretty well. Using entity detection to extract the most common proper and place names did result in plausible settings and casts without any preconceived knowledge of the source material.

- I got much better results extracting noun phrases versus just nouns. Noun phrases take their adjectives and articles along for the ride, ensuring that there's decent grammatical agreement (like using "a" versus "an"). Noun phrases also better preserve the feel of the original work, which is how I ended up with phrases like, "Mulder eats the greenish ooze."

In conclusion, text generation is a world of contrasts. I already knew that a glorified Madlibs approach was unlikely to work well so I'm not too disappointed in the outcome. I have an idea about where to go next with CFGs that should play to their strengths. And I'm definitely not giving up on fanfic! I'll be using it as a way to learn the delicate art of text classification to process some very indelicate prose.

Resources

spacy.io for the named entity recognition and part-of-speech detection. nltk.CFG for initializing the context-free-grammars and generating the productions. Internet Archive for the archive of fanfiction.net. And see Ross Goodwin's Adventures in Narrated Reality for a fun tour of using recurrent neural networks to do similar work.

In the Morning melons often fall and tomorrow separate Blankets will bring me through the willows.

Turn the crowbars today So through The willows my Dog again staggers At home And carefully separate Blankets knead me in the morning.

— Poem generated by RETURNER-THREE-C (Milic, 1970*) after *Alberta Turner

Automatic classification: hot or not?

Having experimented with text generation using context-free grammars, one of the oldest techniques in natural language processing, I turned to classifiers.

Automatic classification is the process by which a computer is trained to categorize an item into one or more defined buckets. A common type of classification is no doubt working on your behalf right this moment: spam filtering. Spam filters are relatively easy to understand because the simplest algorithms work pretty much like a human would:

- Find words that strongly suggest the text is spam, like "Viagra" or, as I found in my current spam folder, "WALMART GIFT CARD".

- If those words are frequently found in a given sample, call it spam.

- There is no step three.

You can do this kind of frequency analysis to solve all kinds of problems. One common classification task is sentiment analysis—identifying whether a statement is positive or negative. Companies use sentiment analysis to understand whether people hate their products on Twitter, or to decide how to escalate your customer service email. The classifier doesn't really know anything about the abstract concept of negativity, just that a review that includes words like, "broken," "disappointed," or "fail" probably aren't praise.

Automatic classification can be applied to more input than just text; neural nets can perform complex image recognition, and advanced AI systems such as self-driving cars use classifiers to identify road signs and hazards. But I'm on the beginner track here, so I'm just learning how to use basic statistical methods on words.

Training a classifier

From the perspective of the end user, the hard work in classification is getting a big-enough training set. You, the human, have to do the computer's work first, by manually classifying a subset of texts and feeding that to the algorithm. I'm generally averse to hard work, so instead I looked for an interesting set of data that was already classified by other people.

I'm sitting on this big corpus of fanfic, and much of it is rated by the authors for its, let's say, family-friendliness. Identifying sexy vs. non-sexy fiction sounded like an intro-to-classification problem that I'd find fun. I would teach a computer to know it when it sees it.

Bags full of words

I found this post useful as a starting tutorial because it had a lot of narrative and it describes how to do many steps by hand. As you'll see in the final code, much of that is boilerplate that can be abstracted away by libraries, but it's useful to understand what's going on.

Many text classification problems can be solved by using the "bag of words" model, in which the algorithm counts how frequently each word occurs in the text but throws out grammar and sentence structure. Word frequency is usually good enough for broad classification problems, though it would fail if I desperately needed to distinguish "You do you" from "You do me." Fortunately this corpus is not particularly subtle.

I wrote a program to segment the fanfic by the authors' content rating: I selected fic rated "NC-17" for my naughty set, and categorized all other ratings as nice. I used X-Files fanfiction as my corpus because I had good exemplars of both categories, and because I'm familiar with it to a somewhat embarrassing degree.

I took a random subset of my training data, plugged in the rest of the tutorial code as best I understood it, and asked the program to predict whether new fanfic it had never seen before was naughty or nice.

Because I am a programmer and not a scientist I assumed that the first answer I got was right and immediately bragged about it on Twitter.

Hooray! But that outcome seemed suspiciously good for someone who didn't really know what they were doing.

"Nobody likes a math geek, Scully."

"You might want to check whether it performed equally well with each class," my husband dansplained. I rejected this possibility because I am an AI genius, and then quietly slunk off to check my work.

Of course it was wrong.

Due to a bug, my classifier was overwhelmingly guessing "nice." And I had failed to account for the fact that (to many people's surprise), the majority of fanfiction is not actually explicit, so about 80% of what I asked it to classify was nice. Multiplying these two errors meant that it was "right" the vast majority of the time. When I actually broke down the results, I saw that it guessed naughty for actual NC-17 works only 62% of the time, not much better than chance.

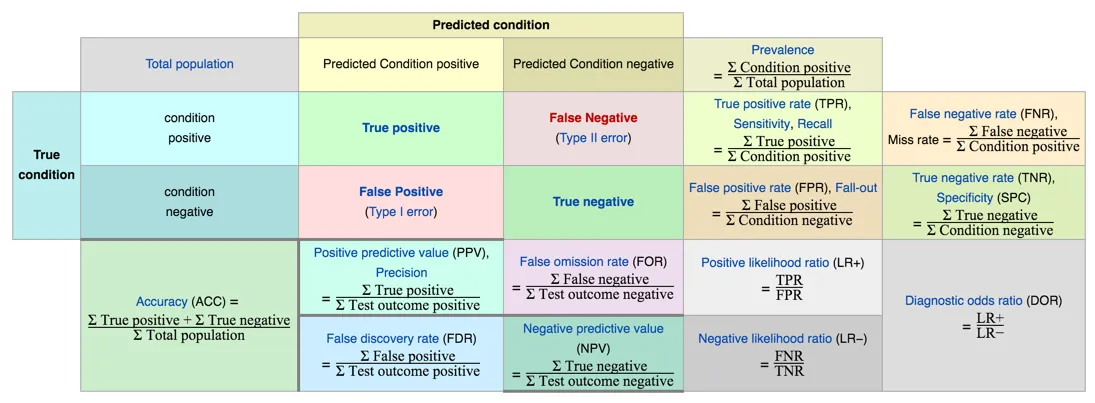

Formally, this problem is defined by the terms precision and recall, helpfully illustrated with this chart:

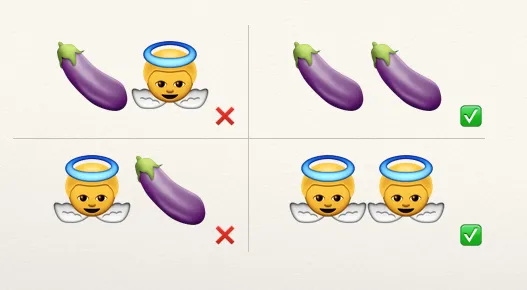

and which I have summarized thusly:

My classifier was great at the lower right quadrant: input was nice, and it guessed nice, therefore it was correct. And it rarely exhibited the error in the lower left: it never guessed naughty when the answer was nice. Where it failed pretty terribly was the upper left, but it got so few naughty samples that my weighted average still came out looking great. I had to go back and figure out why it didn't think enough items were NC-17, and ensure that I when I evaluated my model, both classes were represented equally.

From naughty to nice

I reimplemented my classification pipeline using the methods supplied by the scikit-learn package to clean, ingest, and fit the model to the training set. This tutorial was extremely helpful, and I was able to delete most of my code (always a sign of forward momentum). In the process of the rewrite, I found an ordinary Python typo that had caused my nice training set to accidentally include unrated works, meaning some unlabeled naughty stories were polluting the model.

scikit-learn provides mechanisms to test your model's validity to avoid embarrassing tweets like the one above. After I provided a more accurate training set and experimented with a few different classifying algorithms, I developed a model that was better than chance and good-enough-for-me in all cases:

precision recall f1-score support

nice 0.79 0.90 0.84 2384

naughty 0.87 0.75 0.81 2204

avg / total 0.83 0.83 0.83 4588

And to be really really sure it was operating sanely (and to satisfy my own curiosity), I asked the model which words were most likely to represent each class:

NICE NAUGHTY

-1.3587 hospital 1.9847 alex

-1.1806 cat 1.9310 walter

-1.0641 diana 1.7642 tongue

-0.9795 trees 1.7274 [male chicken]

-0.8878 heart 1.6706 legs

-0.8810 com 1.6598 bed

-0.8685 phone 1.5064 body

-0.8576 car 1.4933 mouth

-0.8465 doctor 1.4454 hips

"Alex" and "Walter" are the first names of male secondary characters, so what this tells me is that I inadvertently wrote a slashfic detector. "Hospital" and "doctor" suggest that the majority of the non-sexual stories were probably hurt/comfort. Overall, looks legit.

Here's the complete final code (assuming two directories of fanfic for training and test data, each with subdirs labeled "naughty" and "nice"):

TL;DR

Basic text classifiers are pretty easy to code in Python, and if you work with large volumes of text, you probably already have problems you could solve with them. Just remember to check your work.

Scully: What do you think? Mulder: I can't believe we put so much faith in machines. — Space

World models: applying order to the procedural universe

NLP is deeply concerned with language models: systems that attempt to represent human language through statistical relationships and/or formal logical grammars. Language models usually don't attempt to represent semantics or otherwise relate language to the real world. Programmers can get pretty far treating language as an abstract logic puzzle, but if you spend any time doing procedural text generation or comprehension, the limitations become obvious.

One way to address this is to layer on a world model: an additional representation of what words mean. Rather than relying solely on how words relate grammatically or probabilistically, it's possible to guide systems towards producing text that is internally consistent and stylistically coherent.

World models aren't often considered part of NLP, and historically researchers have run into dead ends by attempting to apply them. But I think they're worth looking at again, and some of the most interesting work in hybrid NLP/world modeling comes from the videogame community, where world models are routine.

Worlds apart

World models are often left out of NLP discussions because they're unnecessary for many use cases. The simplest possible language model is purely probabilistic: words that co-occur together in a big pile of sentences (a "corpus") are likely to be related. A computer can figure this out just by counting up the words and their adjacent neighbors [example code] and storing them; these are called n-grams, where bigram is a two-word phrase like "shining sun" and trigram is "bright crescent moon" and so on.

That example code takes all the words from 18 classic novels and extracts all the two-word phrases (bigrams) that contain the word sun. I can then rank them in order of frequency and get this tidy list of sun-related phrases—all without the computer understanding anything about the meaning of the word "sun":

>>> [' '.join(result[0]) for result in Counter(sun_bigrams).most_common(10)]

['sun shall', 'setting sun', 'western sun', 'rising sun', 'mr sun',

'sun shining', 'sun rise', 'sun shone', 'sun moon', 'sun rose']

(If, like me, you were curious what classic of literature made prodigious use of "Mr. Sun," I am here for you. As in all models, output is reflective of the input we give it; watch for weird outliers like this in your training data.)

Combining frequency analysis with text generation gives you the ability to generate new sentences that can sound, if not plausible, at least hallucinogenic. The humble Markov chain, applied to linguistics, strings together short phrases like "sun shines", "shines brightly", and "brightly in" to create a kind of computer-generated game of telephone.

This code produced sentences like Sun rise vanished in ashes of weary with the length and Sun just descended in the lord o my sword. These utterances won't win anybody a Booker Prize, but if you're just learning NLP, writing a Markov chain generator is a fun first coding project.

Longer phrases and other tweaks can produce better output: Sun of righteousness thou hast ordained to destroy them and better withstand the fire is pretty bad-ass and I got that just by changing to trigrams. But the longer you make the sequences the less likely they are to truly be original; at some point the computer is just plagiarizing. At best these methods will only generate intelligible sentences, never coherent paragraphs or whole works.

Sense and sensibility

Ideally, a generated text could pass four fitness tests:

- It's grammatically correct: A human should perceive the text as well-formed.

- It makes sense: The text says something meaningful. Chomsky's famous grammatically correct but meaningless Colorless green ideas sleep furiously comes to mind, but beware also of Their unstable behavior drove the car away, which is the kind of thing that a Markov chain might generate. Ideally, avoid these nonsense phrases.

- It fits into a coherent narrative: This test comes into play once we produce texts longer than a single sentence. Does one sentence flow naturally into the next? If our generator produces fiction, are the characters and scenes stable from sentence to sentence?

- It's plausible: Are the events described realistic? Humans certainly break this rule all the time (see: most genre fiction), but for the most part a computer's output shouldn't be on the order of The baseball game was won 305 to 8 or Every day he commuted from Boston to Los Angeles. While these statements are possible, they're vanishingly unlikely to be true.

We can get pretty far meeting test #1 by dumb luck with Markov-like methods, or by constraining output through formal grammars.

Passing #2 is achievable by making use of language models that can distinguish among word senses in context. Just from analyzing enough sentences, a computer can learn that a "car" can be "driven," but only by a noun that maps to a human, and that a human can be "driven", but only by a word that represents a goal or need. This is not yet out-of-the-box NLP, but it's been demonstrated to be a tractable problem. Recurrent neural networks are also pretty good at this (see below) because by definition they're very sensitive to context.

#4 is probably impossible right now, especially for an unconstrained narrative.

#3 is where world models can best help.

A brief digression on recurrent neural networks

I'm not covering neural networks in this series because I don't understand them sufficiently, but it is worth mentioning RNNs as they are (often) good at producing coherent-but-creative output, and (sometimes) good at maintaining a consistent world state. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks is a very readable discussion of RNN text generation; if you hate math just skip to the examples as they're quite fun.

Many worlds

"If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe." — Carl Sagan (1980)

World modeling isn't new in computer-generated writing; if anything, it's one of the oldest techniques, irrevocably bound up in the early experiments in "strong artificial intelligence" that were ultimately seen as a dead end. Early AI research assumed, not unreasonably, that the process of teaching a computer to be more humanlike would resemble the process by which humans teach themselves, starting from simple concepts with explicit rules. (One of many problems with this assumption is that formal instruction accounts for only a fraction of what children learn.)

Early computational text generators were often composed of rules that modeled aspects of the real world; the "generative" component was supplied by user interaction or simply from randomized word lists. A well-studied text generator that made use of an extremely rich world model was Tale-Spin (1976), extensively written about by Noah Wardrip-Fruin in his book Expressive Processing:

The world of Tale-Spin revolves around solving problems, particularly the problems represented by four "sigma-states": Sigma-Hunger, Sigma-Thirst, Sigma-Rest, and Sigma-Sex. These, as one might imagine, represent being hungry, thirsty, tired, and — in the system's terminology — "horny," respectively. — Wardrip-Fruin

End users would set up the parameters of the story: there's a character named Betty, she lives in a forest, her problem is that she's hungry. The program then set up the world model and turned the crank; a story could equally end with the "sigma-state" being satiated, or the character could starve and die. Unfortunately, the nuances of text production were seen as an afterthought — the point was the world model — so the extant output of this now-lost program is pretty boring:

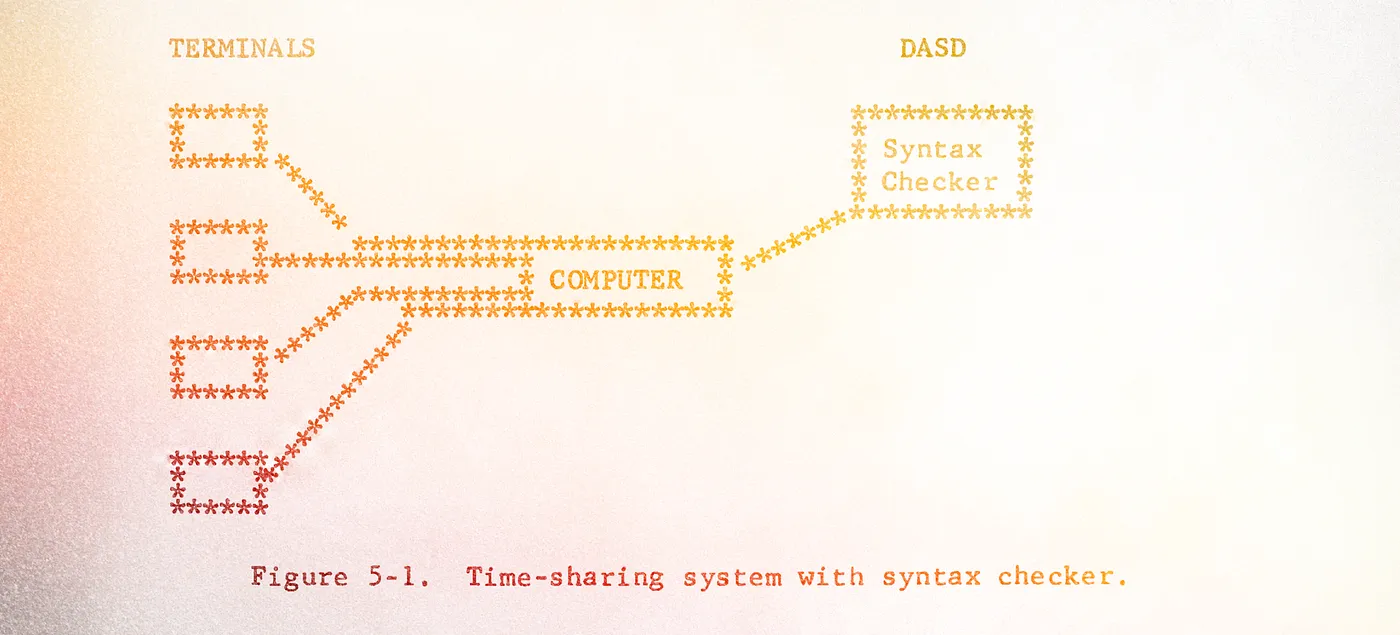

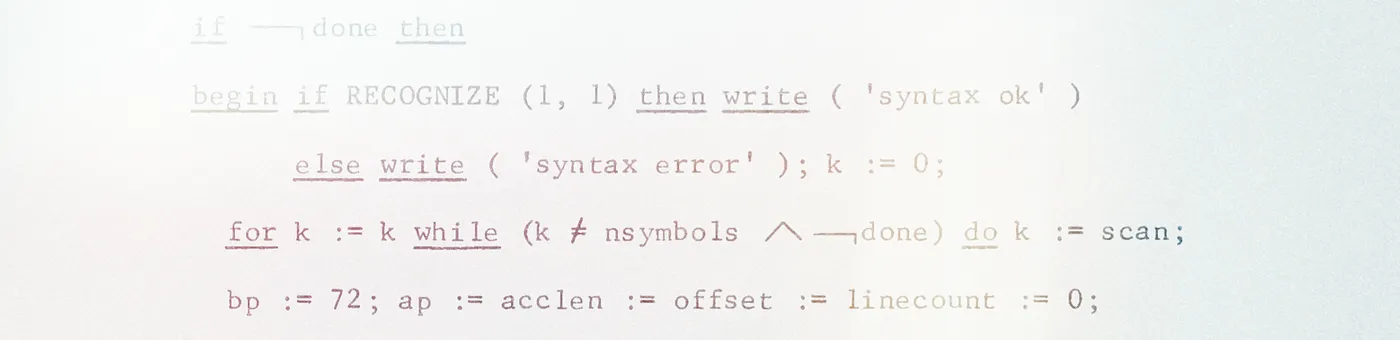

In the 1980s, enthusiasm for rule-based AI waned, and rule-based generative authoring faded out too. One problem was that making the simulacra more real meant ever-larger rulesets, and computing power of the time couldn't scale to accommodate (Tale-Spin ran just under the absolute memory limit of Yale's timeshare computer — at 75K). It also became obvious that relying entirely on a hand-crafted world model was a fool's errand.

Interest in procedurally generated text is picking up again now, but mostly in the form of straightforward outputs of recurrent neural nets. While they can be super fun, they still can't produce anything close to a true "story."

Model citizens

Most videogames include characters that the player doesn't directly control (NPCs). Even in the simplest games, NPCs are governed by rules, usually fuzzed with a little randomness to make them seem less robotic. Take Pac-Man: the ghosts search for Pac-Man, follow him if "seen", run away from him if he's eaten the energy pill. Each ghost has a slight tweak to its algorithm to give it a distinct "personality." The game would be less effective if their behavior was entirely random.

Because videogames are closed worlds, it's possible (though still difficult!) to completely model the interactions among semi-autonomous entities in a way that's believable enough for a game. Spend enough time in a sandbox-style game like Grand Theft Auto and you'll observe passers-by acting out miniature dramas without human intervention. Videogame AI, which is, arguably, not artificial intelligence at all, does demonstrate that rule-based systems can generate convincing behavior that, in specific contexts, are good enough without having to first invent the universe.

So it's not surprising that many people working on hybridizing model-based AI and creative text generation come from the interactive fiction community, which has always occupied the space between inventing new narratives and crafting quality prose.

Getting an infinite number of lamps

I need a toolkit for generating text that appears human, that respects an underlying world model, and that can be used at significant scale — to produce hundreds of thousands or even millions of words — by a person who thinks of herself primarily as an author. — Emily Short (2015)

The Annals of the Parrigues by Emily Short is one of my favorite procedural works; it's both delightful to read and internally consistent. By introducing randomness but applying constraints, she was able to create a unified work of a scale that was impractical to author by hand. And that same randomness opened the door for unintentional wry humor on the part of the algorithm:

The town is best known as the tomb of Alianor Espec II, an orphan who came to the town fleeing charges of presentation of obscene performance in her hometown. There is a very fine volume that recounts the entire affair, with hand-drawn illustrations.

It's worth reading her endnotes from the work [PDF] in full, in which she documents the salient features of the world model and other examples of the "creativity" of the computer.

Bruno Dias, the author of the excellent hypertext game Cape, has also spoken about combining procedural text with a fact-based model:

In games, procgen originated as a workaround for technical limitations, allowing games like Elite to have huge galaxies that never actually had to exist in the limited memory of a 90's computer. But it quickly became an engine of surprise and replayability; roguelikes wouldn't be what they are if the dungeon wasn't different each time, full of uncertainty. Voyageur represents an entry into what we could call the "third generation" of procgen in games: procedural generation as an aesthetic. — Dias

There are others applying world models (or at least logical constraints) to generated text: one of the first NaNoGenMo novels, Teens Wander Around a House (2013) by Darius Kazemi, pours Twitter-sourced text into a model of a suburban house; The Seeker (2014) by thricedotted (also a NaNoGenMo work) generates it own model and then writes from it; and there's a resurgent interest in formal goal-centric world modeling (though much of this work is locked behind academic publishing paywalls).

Conclusion

Though I'm most interested in procgen text as art, there's value in aesthetically pleasing generated text in any NLP context: more engaging chatbots, richer automated document summaries, or new ways to model literature in digital humanities research. Imagine if machine translation could self-correct implausible utterances, or those which are contextually inappropriate.

It's okay, and even maybe desirable, if the fingerprints of the machine are still present in its output. People working on procedural art aren't looking to replace artists, but to augment them. A chatbot that was indistinguishable from a human would in many ways be the least interesting chatbot of all. It's the unfettered id of the computer filtered through the editorial and artistic goals of the human where the real magic lies.